Did Alien Life Evolve Just After the Big Bang?

Earthlings may be extreme latecomers to a universe full of life, with alien microbes possibly teeming on exoplanets beginning just 15 million years after the Big Bang, new research suggests.

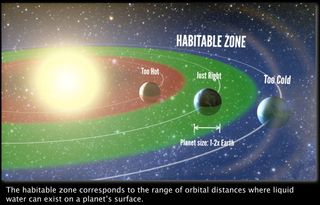

Traditionally, astrobiologists keen on solving the mystery of the origin of life in the universe look for planets in habitable zones around stars. Also known as Goldilocks zones, these regions are considered to be just the right distance away from stars for liquid water, a pre-requisite for life as we know it, to exist.

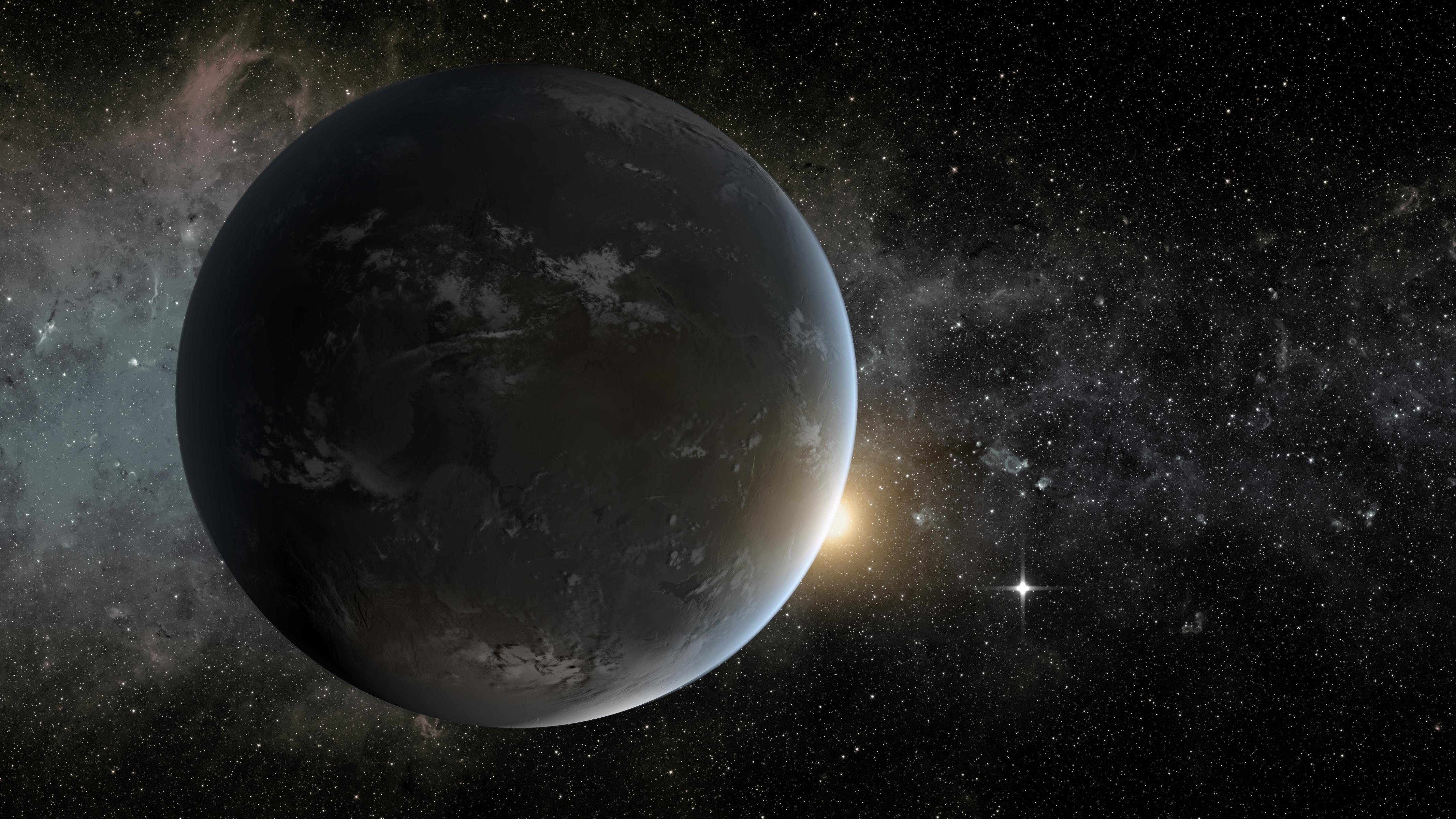

But even exoplanets that orbit far beyond the habitable zone may have been able to support life in the distant past, warmed by the relic radiation left over from the Big Bang that created the universe 13.8 billion years ago, says Harvard astrophysicist Abraham Loeb. [The Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps]

For comparison, the earliest evidence of life on Earth dates from 3.8 billion years ago, about 700 million years after our planet formed.

'Warm summer day'

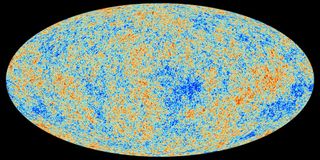

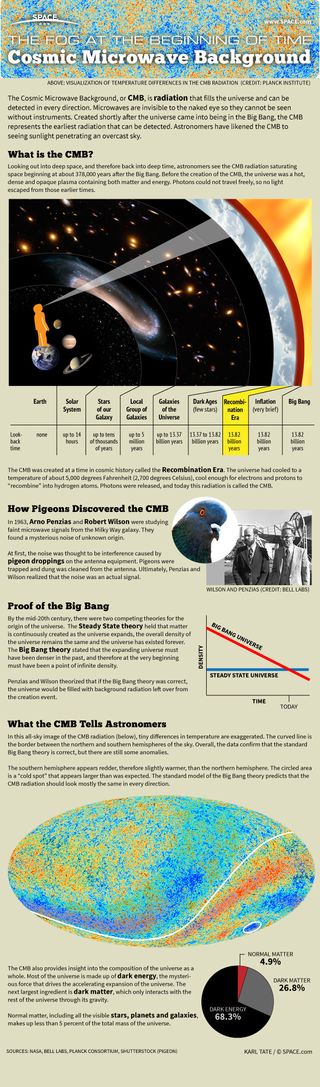

Just after the Big Bang, the cosmos was a much hotter place. It was filled with sizzling plasma — superheated gas — that gradually cooled. The first light produced by this plasma is the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB) that we observe today, which dates from about 389,000 years after the Big Bang.

Now the CMB is freezing cold — around minus 454 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 270 degrees Celsius; 3 Kelvin). It cooled down gradually with the expansion of the universe, and at some point during the cooling process, for a brief period of seven million years or so, the temperature was just right for life to form — between 31 and 211 degrees Fahrenheit (0 and 100 degrees Celsius; 273 and 373 Kelvin).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It is the CMB's heat that would have allowed water to remain liquid on ancient exoplanets, Loeb said.

"When the universe was 15 million years old, the cosmic microwave background had a temperature of a warm summer day on Earth," he said. "If rocky planets existed at that epoch, then the CMB could have kept their surface warm even if they did not reside in the habitable zone around their parent star." [Gallery: Planck Spacecraft Sees Big Bang Relics]

But the question is whether planets — and especially rocky planets — could already have formed at that early epoch.

According to the standard cosmological model, the very first stars started to form out of hydrogen and helium tens of millions of years after the Big Bang. No heavy elements, which are necessary for planet formation, were around yet.

These first planets would have been bathed in the warm CMB radiation, and thus, Loeb argues, it would have been possible for them to have liquid water on their surface for several million years.

Loeb says that one way to test his theory is by searching in our Milky Way galaxy for planets around stars with almost no heavy elements. Such stars would be the nearby analogues of the early planets in the nascent universe.

Constant or not?

Based on his findings, Loeb also challenges the idea in cosmology known as the anthropic principle. This concept attempts to explain the values of fundamental parameters by arguing that humans could not have existed in a universe where these parameters were any different than they are.

So while there might be many regions in a bigger "multiverse" where the values of these parameters vary, intelligent beings are supposed to exist only in a universe like ours, where these values are exquisitely tuned for life.

For instance, Albert Einstein identified a fundamental parameter, dubbed the cosmological constant, in his theory of gravity. This constant is now thought to account for the accelerating expansion of the universe.

Also known as dark energy, this constant can be interpreted as the energy density of the vacuum, one of the fundamental parameters of our universe.

Anthropic reasoning suggests that there might be different values for this parameter in different regions of the multiverse — but our universe has been set up with just the right cosmological constant to allow our existence and to enable us to observe the cosmos around us.

Loeb disagrees. He says that life could have emerged in the early universe even if the cosmological constant was a million times bigger than observed, adding that "the anthropic argument has a problem in explaining the observed value of the cosmological constant."

Edwin Turner, a professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University, who was not involved in the new study, called the research "very original, stimulating and thought-provoking."

Astrophysicist Joshua Winn of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who did not take part in the study either, agrees.

"In our field, it has become traditional to adopt a definition of a 'potentially habitable' planet as one that has a solid surface and a surface temperature conducive to liquid water,” he said. "Many, many papers have been written about the exact conditions under which we might find such planets — what type of interior composition, atmosphere, and stellar radiation field. Avi has taken this point to a logical extreme, by pointing out that if those two conditions are really the only important conditions, then there is another way to achieve them, which is to make use of the cosmic microwave background."

Loeb's paper is available at http://arxiv.org/abs/1312.0613

Follow Katia Moskvitch on Twitter @SciTech_Cat. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Katia Moskvitch is a freelance science writer based in Switzerland currently serving as the head of communications for IBM Switzerland. She an award-winning writer who has covered astrophysics and other topics for Space.com, with her work also appearing in Quanta Magazine, Science, Wired, BBC News, Scientific American and The Economist among others.

In 2019, Katia was named European Science Journalist of the Year as well as British Science Journalist of the Year, and her book "Neutron Stars: The Quest to Understand the Zombies of the Cosmos" was published by Harvard University Press in September 2020. Katia holds a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from McGill University and master's degrees in journalism from the University of Western Ontario and in theoretical physics from King's College in London. She is fluent in English, French and Russian.